Most people know massage feels good. What fewer realize—especially here in the U.S.—is how much real, measurable benefit it can have on your health. In places like Norway or much of Western Europe, massage is often seen as a regular part of staying well, not just an occasional treat. But in America, it’s still mostly viewed as a luxury or indulgence. The reality? Massage can help with chronic pain, poor sleep, anxiety, and even immune function. If you’ve ever walked away from a session feeling clearer, calmer, or more at home in your body, that wasn’t just in your head. There’s solid research behind those effects—and for a lot of people, massage is more than relaxation. It’s part of how they stay healthy.

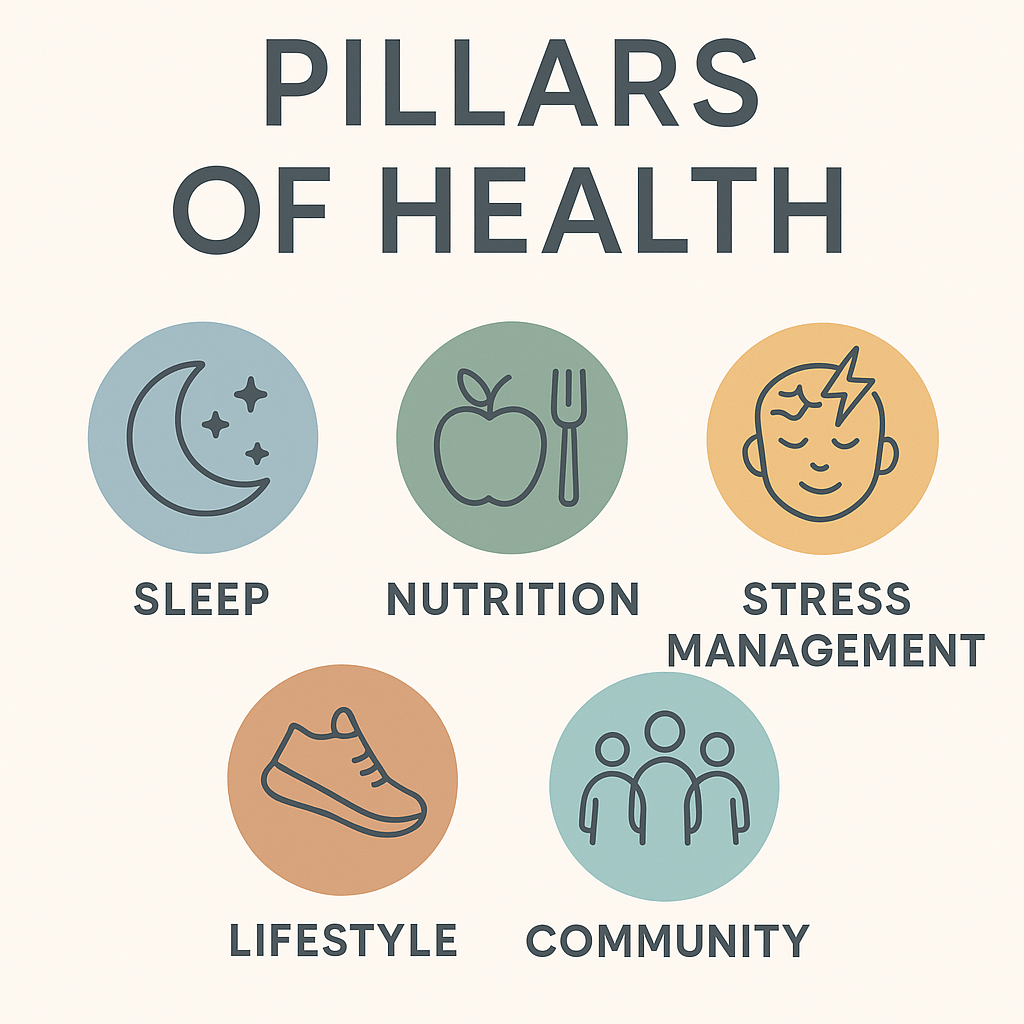

1. Reduces Stress and Lowers Cortisol

Massage therapy has been shown to significantly reduce cortisol levels and increase serotonin and dopamine.

[Field, 2005 – Int J Neurosci]

[Rapaport et al., 2010 – J Altern Complement Med]

2. Alleviates Muscle Tension and Improves Range of Motion

Regular massage decreases muscle stiffness and improves joint flexibility, supporting athletic recovery and injury prevention.

[Weerapong et al., 2005 – Sports Med]

3. Improves Sleep Quality

Massage has been shown to improve both the depth and duration of sleep, including an increase in delta wave activity—the kind linked to deep, restorative rest.

[Richards et al., 2000 – J Clin Rheumatol]

[Field et al., 1998 – Early Hum Dev]

4. Reduces Pain—Both Acute and Chronic

Massage can reduce chronic low back pain, neck pain, fibromyalgia symptoms, and postoperative pain.

[Furlan et al., 2008 – Cochrane Review]

[Moyer et al., 2004 – Pain Med]

5. Supports Mental Health: Anxiety & Depression

Massage therapy can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, likely via nervous system regulation and oxytocin release.

[Moyer et al., 2004 – Psychol Bull]

[Field et al., 1996 – Int J Neurosci]

6. Boosts Immune Function

Massage may enhance immune markers like natural killer cells and lymphocyte count—particularly helpful in people under stress.

[Field et al., 2005 – J Altern Complement Med]

Final Thoughts

Whether you’re in pain, managing stress, or simply trying to stay well, massage therapy can be a valuable part of your routine. For anyone looking to prioritize feeling better, massage is a surprisingly prudent choice as a regular therapy.