Probably one of the most common questions I get asked is: What do you think of dry needling? Or do you provide dry needling?

It’s a complicated thing to answer because I think there are two valid ways to see it.

The Legal & Scope-of-Practice Angle

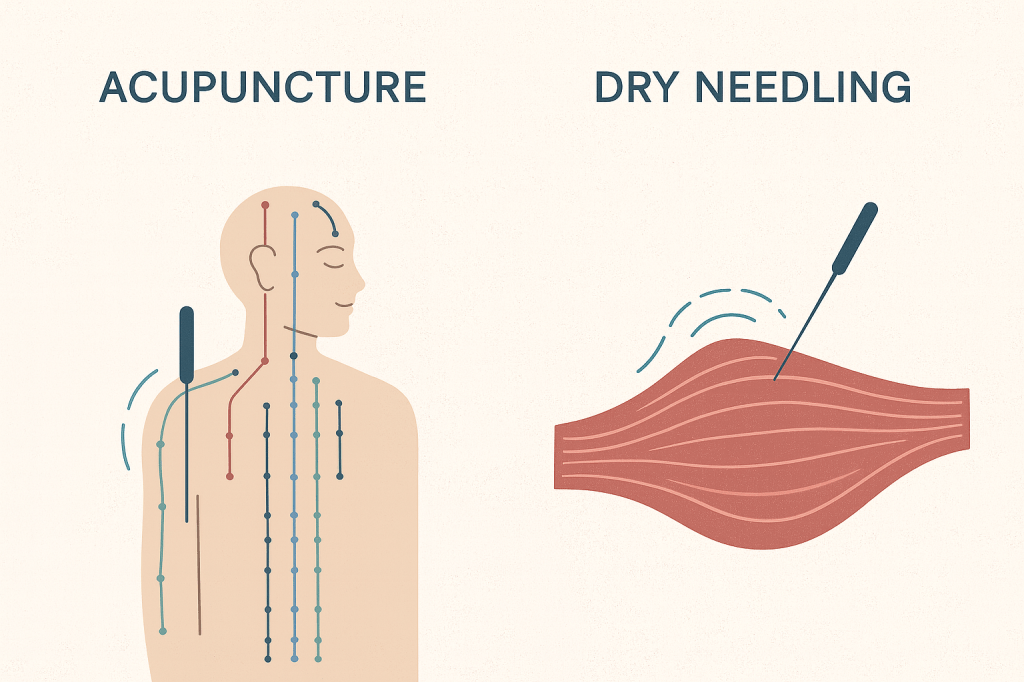

As of writing, dry needling is illegal in California, Hawaii, New York, Oregon, and Washington. The essential issue is this: I don’t take a weekend course in chiropractic adjustments and call myself a “dry chiropractor” or “holistic joint manipulator” or something of the sort.

The primary argument against dry needling, as I understand it, is that the requirements for training aren’t stringent enough to ensure safe and effective treatment. Acupuncture licensure includes extensive training for years to make sure we can insert needles into people in ways that are consistently safe and beneficial.

There’s also the financial reality: it’s an encroachment on scope of practice that acupuncturists mostly deal with because they’re under-represented in a lobbying sense in most states.

But That’s Not the Whole Story

All that said, I don’t think the legal debate tells the full truth. I believe it is possible for a physical therapist or chiropractor to put in the time and effort to genuinely perform dry needling in a way that is safe and helpful.

In my clinical opinion, there is something beneficial about specifically targeting muscle tension through trigger points or neuromuscular junctions—without necessarily needing to interpret the more subtle energetic connections that traditional acupuncture focuses on.

Some acupuncturists even take dry needling classes for this reason: to supplement their traditional training with a more Western, physiology-based approach to the body, especially around trigger points and fascial connections. Traditional acupuncture is deeply enmeshed in Chinese herbal theory and an extremely detailed mapping of the energetic body. It’s rich—but it can also be overwhelming when sometimes you just want to get a spasmed muscle to relax.

Do I Do Dry Needling?

When people ask if I do dry needling, I say yes. I’m more than capable of palpating trigger points and treating them. I mainly let people know that I use a more subtle, gentle technique than most dry needlers. I say this based on both my own experience receiving dry needling and the experiences patients share with me.

Dry needling techniques can often be overly aggressive and, at times, can feel re-traumatizing rather than creating a consistently positive healing experience.

My Main Gripe: The “No Pain, No Gain” Mindset

Assuming someone doing dry needling is being safe about it, my real issue is that the intensity of the technique sometimes scares people away from acupuncture altogether. I’ve had many patients tell me they were afraid to try acupuncture because of a previous dry needling experience.

So then I have to educate: while acupuncture can come with some sensation, the intensity is much lower, and many patients feel little to nothing during an effective treatment. It is possible to resolve pain without causing pain.

Where I Land

So that’s my opinion overall. If I had to pick a side, I prefer a generous approach. I’d love to share this practice, and ideally more people would have access to safe, effective treatments to reduce pain.

I’d prefer more training and a shift in perspective—one that considers the nervous system as much as the tissue—so as to avoid treatments that feel like re-injury. But if pressed, I wouldn’t reduce access to acupuncture or to its relatively new Western spin-off: dry needling.